Behind the Blue:

My internship experience at the Conservation Lab

at the Michael C. Carlos Museum

By Markaila Farnham

During my final semester at Emory in the spring of 2021, I had the pleasure of interning in the Parsons Conservation Laboratory at the Michael C. Carlos Museum. As a double major in Chemistry and Art History, I hoped to create a culminating experience that combined my two seemingly disparate interests. The Conservation Lab at the Carlos Museum was the answer to my musings. Behind the scenes of many museums, there are conservators whose responsibility is to conserve, repair, and prepare works of art for storage, research, or exhibit. Knowledge of chemistry and art materials is required and may be used to study and preserve the objects. Using science to understand the materials and context of an object appealed to me.

Given my background in art history and chemistry and my interest in African Art, Chief Conservator Renée Stein suggested a project to research blue colorants on objects from northwest and central Africa. African art curators have commonly referred to a bright electric blue on African art objects as “laundry blue” and a dark blue as “indigo,” based solely on appearance to the naked eye and without any supporting scientific evidence. In addition to clarifying the materials present, results from this study could potentially help indicate any regional, temporal, or cultural variations in the use of selected blue compounds.

Female Twin Memorial Figure, Ere Ibeji. Nigeria, Africa, early 20th Century. Wood, pigment. Ex coll. William S. Arnett.

Female Twin Memorial Figure, Ere Ibeji. Nigeria, Africa, early 20th Century. Wood, pigment. Ex coll. William S. Arnett.

Female Twin Memorial Figure, Ere Ibeji. Nigeria, Africa, early 20th Century. Wood, pigment. Ex coll. William S. Arnett.

Agbogho Mmuo (Maiden Mask). Nigeria, Africa, mid 20th Century. Wood, pigment, yarn. Ex coll. Graham and Maryagnes Kerr, United States.

Agbogho Mmuo (Maiden Mask). Nigeria, Africa, mid 20th Century. Wood, pigment, yarn. Ex coll. Graham and Maryagnes Kerr, United States.

One of my favorite parts of the project was meeting with Dr. Amanda Hellman, the Curator of African Art at the Carlos Museum, and also with a graduate student from UCLA who was researching the same topic. These virtual meetings were very helpful in exchanging information and resources. One of the touchstone articles for this project was Nancy Odegaard’s “Laundry Bluing as a Colorant in Ethnographic Objects.” Although commonly said to contain the synthetic pigment Prussian Blue, the composition and preparation of laundry bluing vary widely and may include soluble and/ or insoluble colorants. Odegaard provides an overview of the many blue colorants used in laundry bluing and describes its use in the decoration of traditionally manufactured materials throughout the world.

Agbogho Mmuo (Maiden Mask). Nigeria, Africa, mid 20th Century. Wood, pigment, yarn. Ex coll. Graham and Maryagnes Kerr, United States.

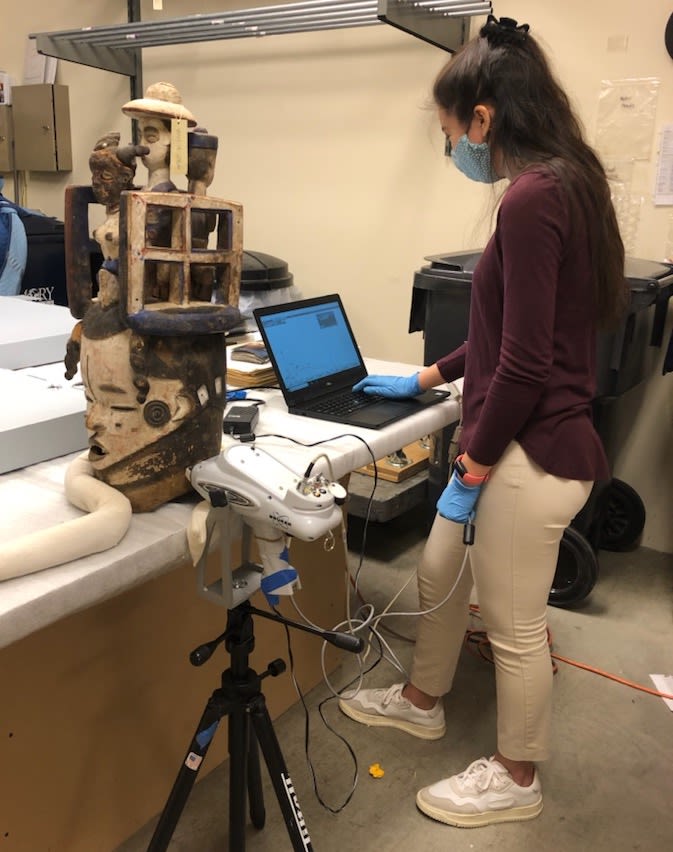

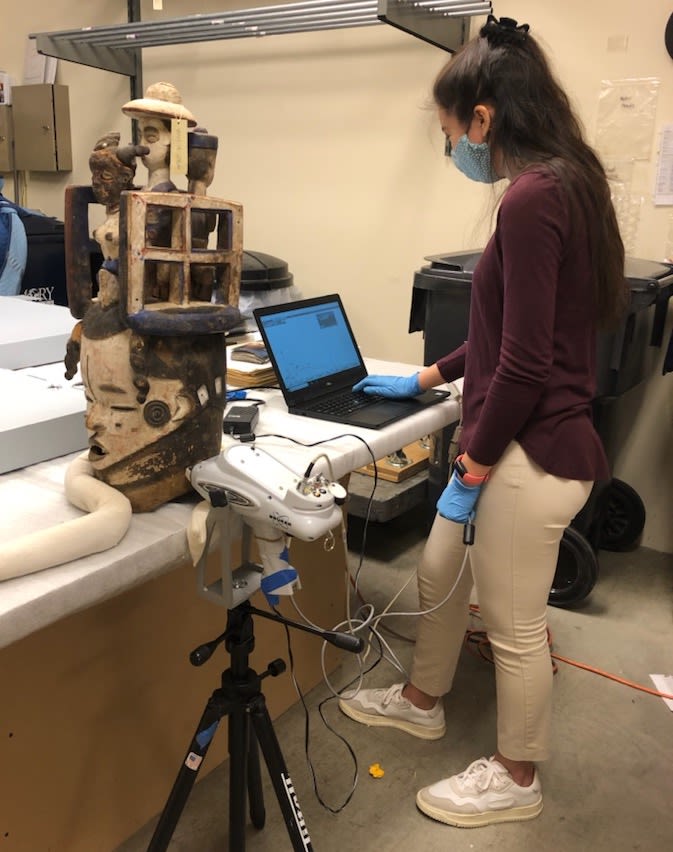

An incredible aspect of this internship was the opportunity to work directly with a conservator, learning from her knowledge and expertise. We met regularly to examine and analyze objects in the conservation lab and storage. I was able to gain experience with light microscopy, x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and microchemical wet testing.

Collecting XRF data from a mask at offsite storage.

We selected 25 objects for investigation and began with XRF spectrometry to determine the elemental composition of the blue colorants. This technique is non-destructive, which means that we didn’t need to remove any samples from the objects and the process of analysis leaves the object unaltered. XRF spectra were collected for both the blue colorant and the underlying wood, recording the major, minor, and trace elemental peaks. This initial data revealed varying amounts of iron (Fe) in each of the blue colorants, perhaps suggesting the presence of Prussian blue, which has the chemical formula Fe4(Fe(CN)6)3.

Collecting XRF data from a mask at offsite storage.

Collecting XRF data from a mask at offsite storage.

Based on the results of this survey, we narrowed our selection of objects for further analysis. In particular, we focused on objects with bright blues and dark blues, as well as those that had “unusual” XRF spectra, while also trying to cover a range of cultures and object types. A sub-set were ibegi, carved twin figures that are often said to be painted with laundry bluing. We then collected physical samples of the blue colorants for use in other experimental techniques. We used a small scalpel to remove tiny amounts of the blue colorants and placed them onto glass slides. Delicately holding the scalpel in my hand, I aimed to inflict the least amount of destruction possible in order to maintain the object’s integrity. I could not help but think of how one day, with my interest in a medical career, I may find myself handling a scalpel with a similar measure of respect for the human body.

We viewed the slides under a stereobinocular microscope and took photographs of each sample, noting physical properties (e.g. color, texture, particle size, etc.). We also viewed and photographed a few samples under a polarizing light microscope (PLM), observing how light interacted with the individual particles and comparing features such as cleavage or refractive indices. Some optical properties are characteristic of specific colorants. Viewed under magnification, some of the samples looked like colored ink dispersing in water and others looked like sparking jewels.

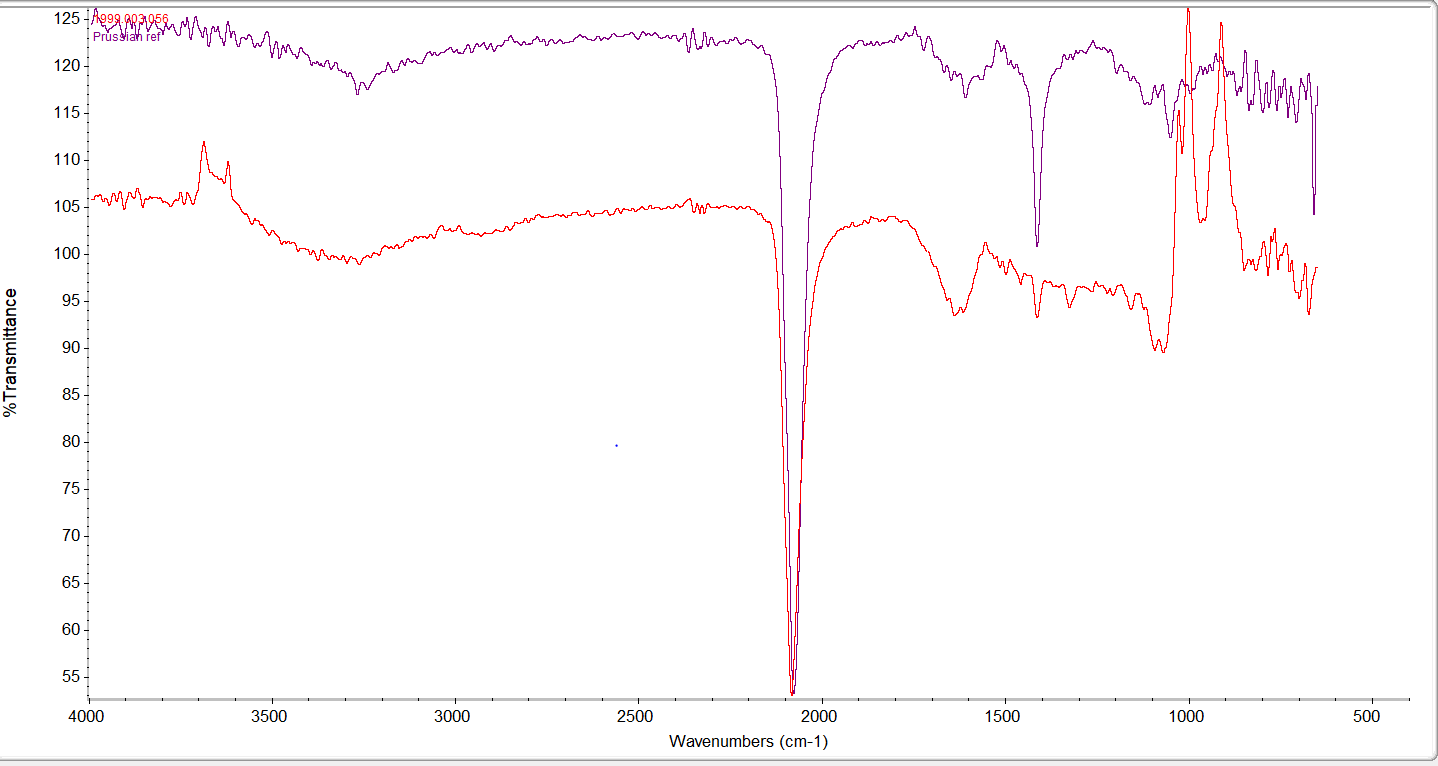

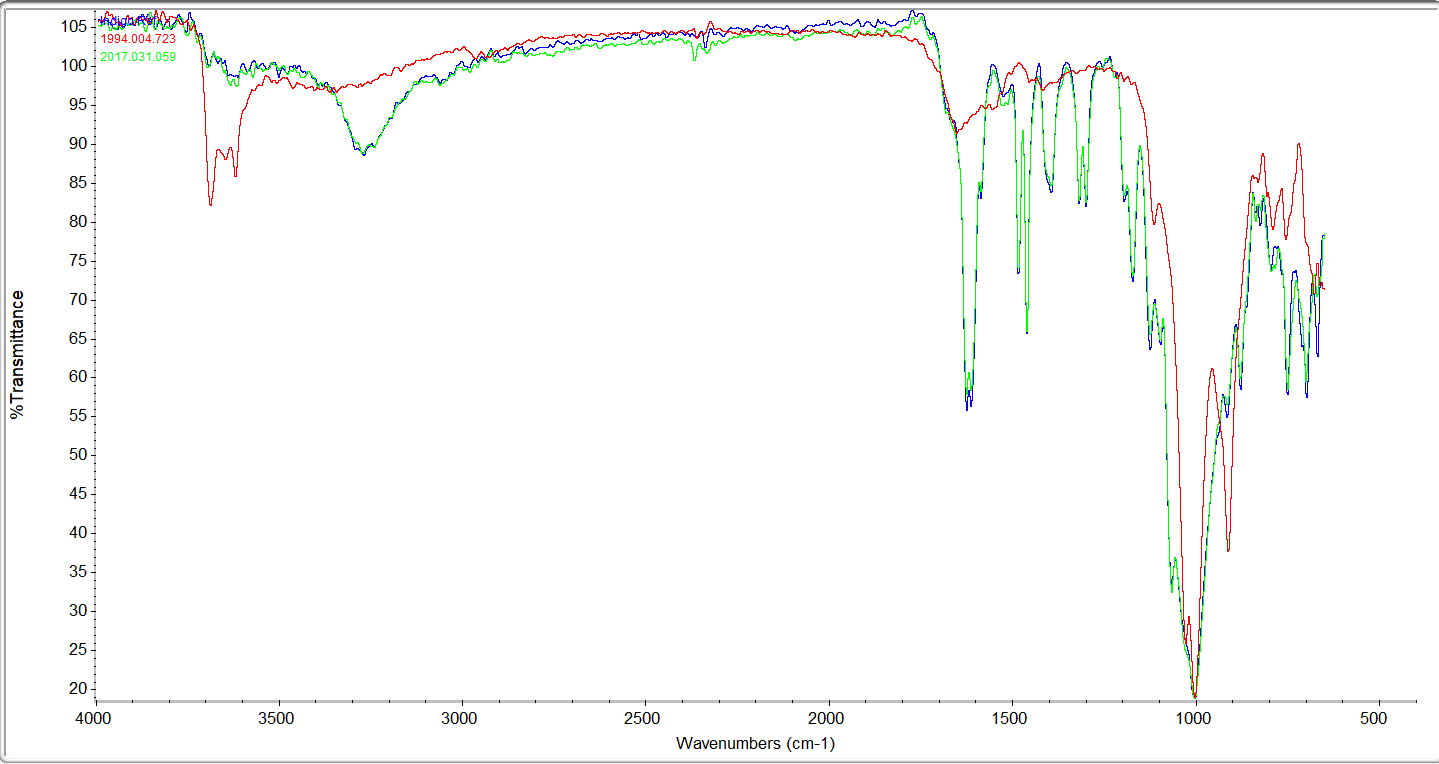

After performing an inconclusive microchemical wet test to assess the presence of indigo, we moved to FTIR spectroscopy, a technique that detects functional groups of molecules and characterizes covalent bonding information. First, we collected reference spectra from known Prussian blue and indigo samples for comparison with spectra from our samples. The results of were somewhat surprising. The preliminary XRF analyses had identified iron on many objects, perhaps suggesting the frequent presence of Prussian blue. However, only one bright blue sample had a strong peak matching the Prussian blue reference spectrum (fig. 2). Two of the bright blues and several of the dark blues matched well with the indigo reference (fig. 3). Several samples revealed peaks seen in both reference spectra, so could be mixtures of both blues.

Fig. 2: Spectrum from a museum object (red) compared with spectrum from a reference sample of Prussian blue (purple). The strong peak at approximately 2100cm-1 is characteristic of Prussian blue.

Fig. 2: Spectrum from a museum object (red) compared with spectrum from a reference sample of Prussian blue (purple). The strong peak at approximately 2100cm-1 is characteristic of Prussian blue.

Fig. 3: Spectrum from a reference sample of indigo (blue) compared with two spectra from museum options (red and green).

Fig. 3: Spectrum from a reference sample of indigo (blue) compared with two spectra from museum options (red and green).

We obtained valuable results in our semester of research, and there is still work to be done, perhaps through further study by the graduate student I had consulted. As anyone who has done any sort of research knows, the process is time-consuming. While chemistry lab classes are often geared toward following an established procedure, with an expected result in mind, we continually adjusted our procedures as we learned more about our samples. I have always found this kind of critical thinking and problem-solving to be part of the allure of research.

Markaila Farnham preparing to sample two ibeji in the Parsons Conservation Lab

Markaila Farnham preparing to sample two ibeji in the Parsons Conservation Lab

I appreciated how this experience enabled me to apply my chemistry knowledge in new and unexpected ways. I also value this experience in the Parsons Conservation Lab because it exposed me to an often-unseen aspect of museum work. Many people are unaware of the chemical research involved in understanding the materials, conditions, and cultural origins of works of art. I hope that future Emory students, especially in the sciences, will seek out the amazing resources available at the Carlos Museum and in the art history department. Given my eye-opening internship experience, I strongly encourage students to find creative ways to combine seemingly disparate fields and interests.

Markaila Farnham preparing to sample two ibeji in the Parsons Conservation Lab