Peering into Power

Researching the Construction of a Kono Helmet Mask

This Kono helmet mask (1994.4.95) entered the Carlos Museum’s collection in 1994 with very little information about its origins or materials. During the 2016 reinstallation of the African galleries, this mask was off display and available for technical study that could reveal details about how the mask was made. As an undergraduate student, I was excited to learn more about the object through a research project in the Parsons Conservation Laboratory, building on my studies of African Art with Dr. Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi of the Emory Art History Department.

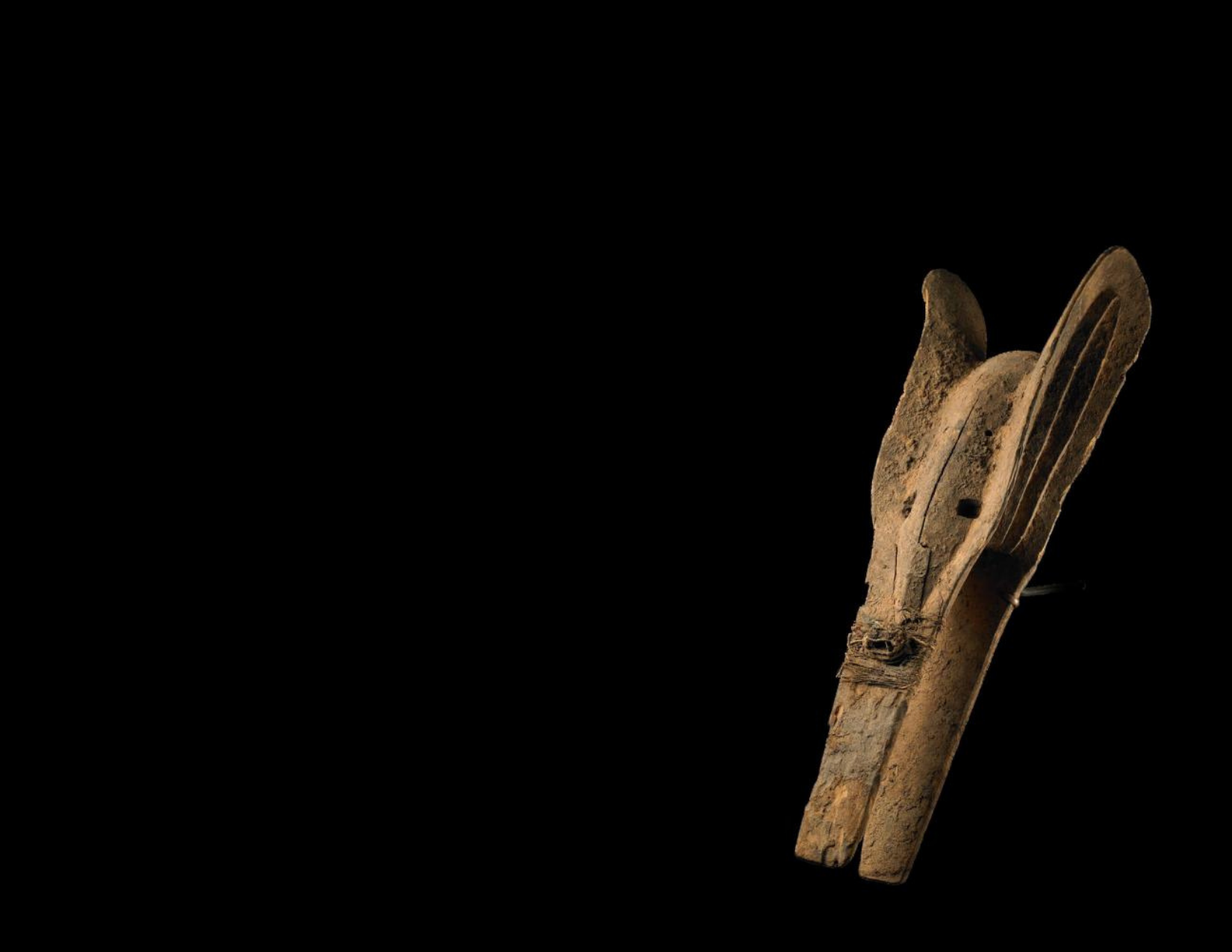

c. 1910 image of a man wearing a Kono helmet mask. Note that the mask sits on top of the head and does not cover the performer’s face. (Ross Archive of African Images, Yale University Library)

c. 1910 image of a man wearing a Kono helmet mask. Note that the mask sits on top of the head and does not cover the performer’s face. (Ross Archive of African Images, Yale University Library)

Kono is one of many power associations active across cultural and linguistic groups in the West African countries of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Côte d’Ivoire. Leaders of the organizations share knowledge with each other and work to help people manage everyday problems. They also create helmet masks and other accumulative objects through repeated applications of surface coatings over many years. These objects demonstrate the leaders' experience with restricted knowledge of the Kono association, and their skill in resolving practical and supernatural problems. As Kono leaders add to and rework helmet masks over the course of their practice, power concentrates in the applied surfaces and in other attachments.

Kono objects are significant because of the secret knowledge that goes into constructing them. As conservators, it is important to respect the secrecy involved in objects like this one. It’s also important to learn what we can in order to recognize the knowledge of the object’s makers. Museum labels generally describe the surfaces of Kono objects as "mud" or "sacrificial materials," which doesn't convey the intent with which the objects are made and augmented.

The Carlos’ helmet mask is carved from wood and has a surface coating built up through multiple applications. We removed a sample of wood roughly half an inch long and an eighth of an inch wide from the mask’s underside. The Center For Wood Anatomy Research identified the wood as Gold Coast bombax, a tree native to West Africa.

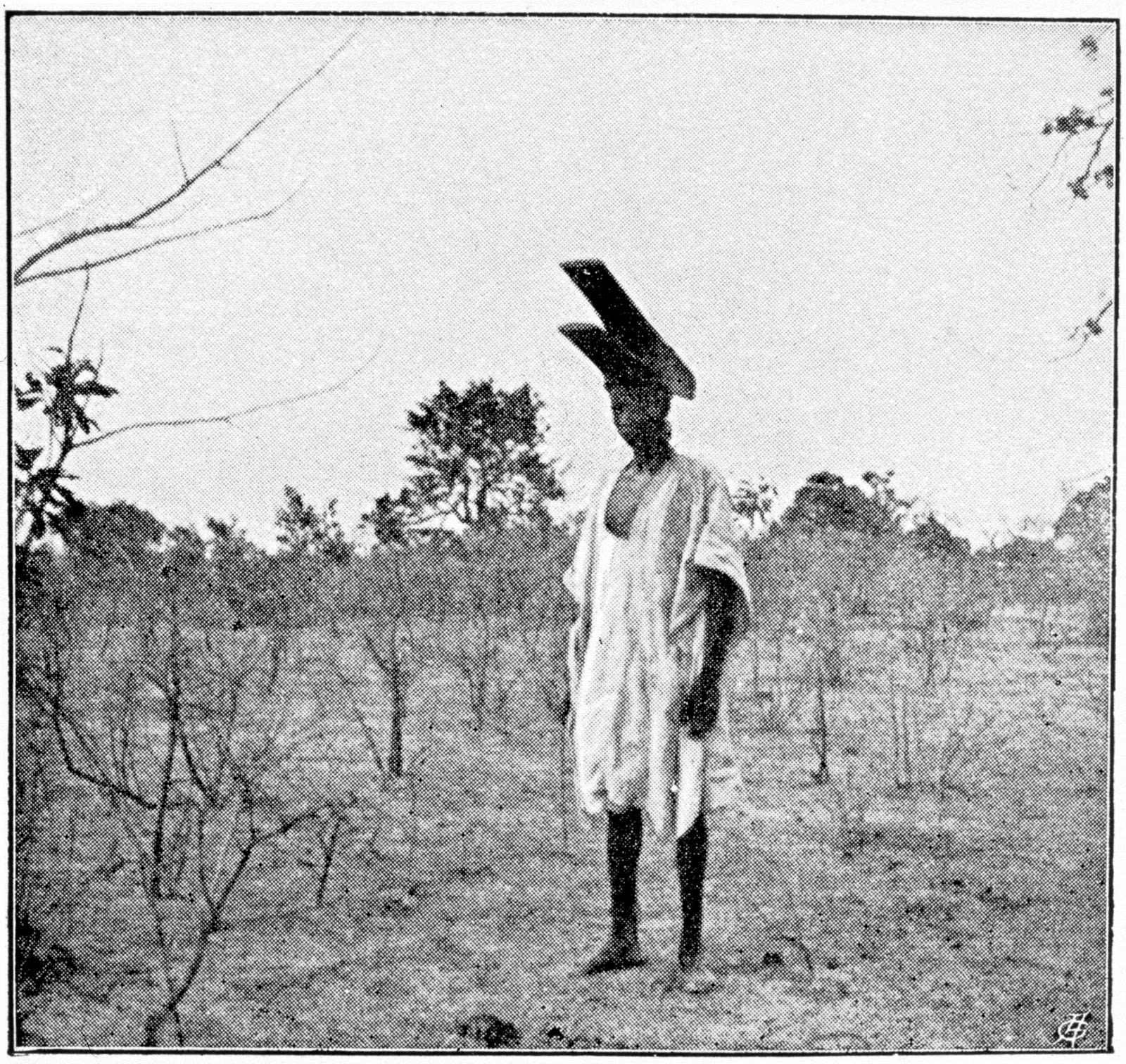

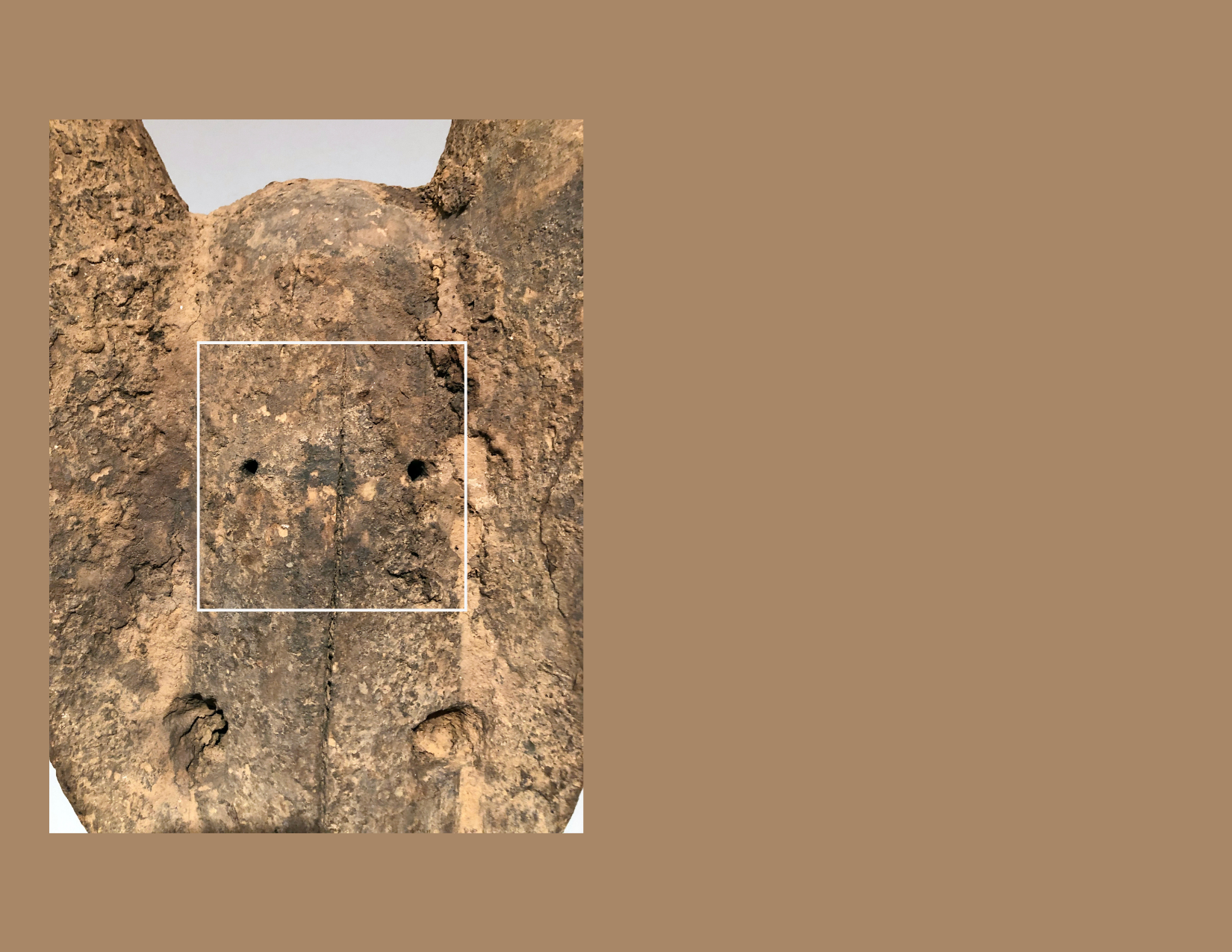

Detail of surface layers on Kono mask at proper right ear.

Detail of surface layers on Kono mask at proper right ear.

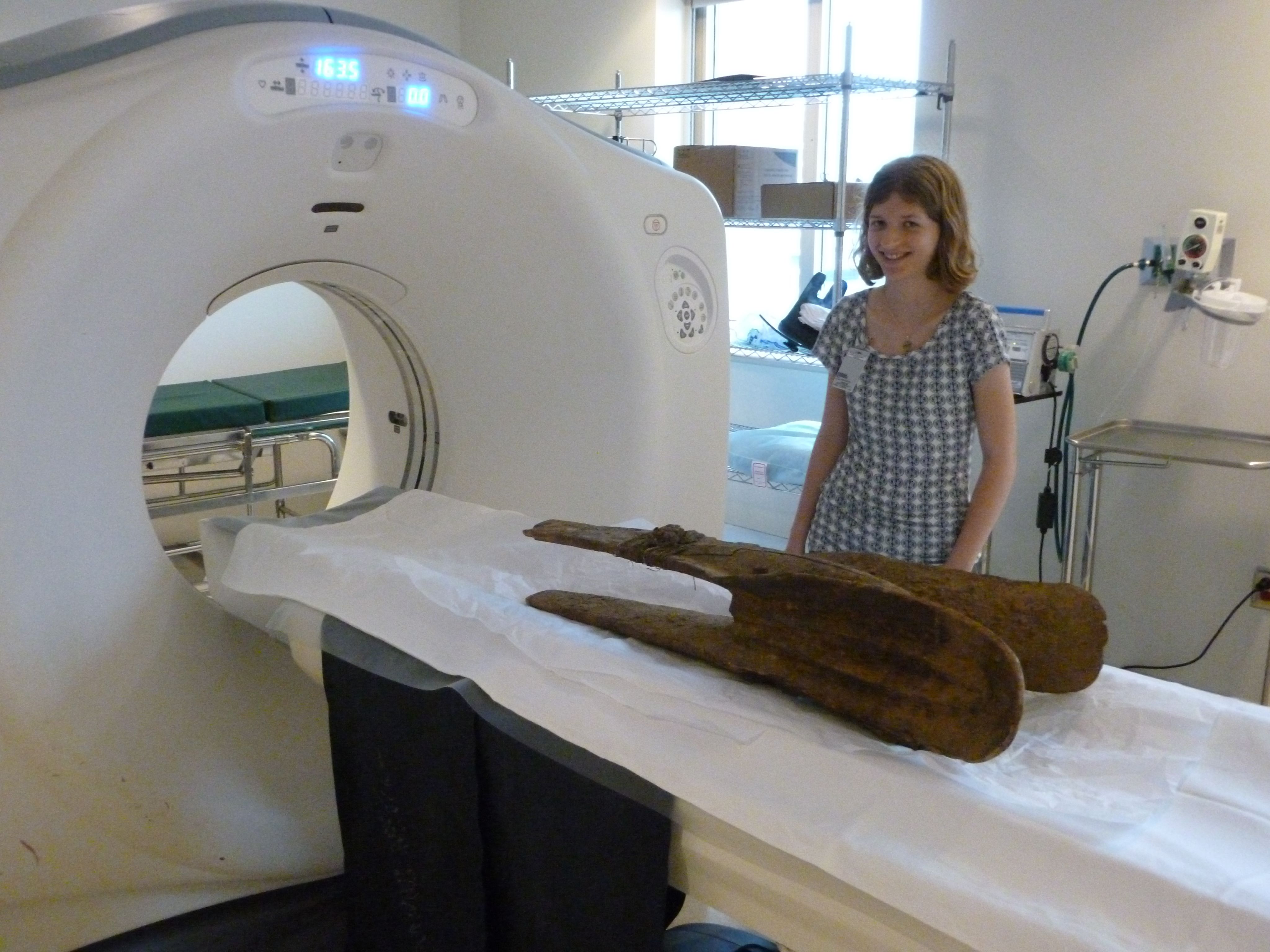

Sarah Lindberg with CT scanner at Grady Hospital.

Sarah Lindberg with CT scanner at Grady Hospital.

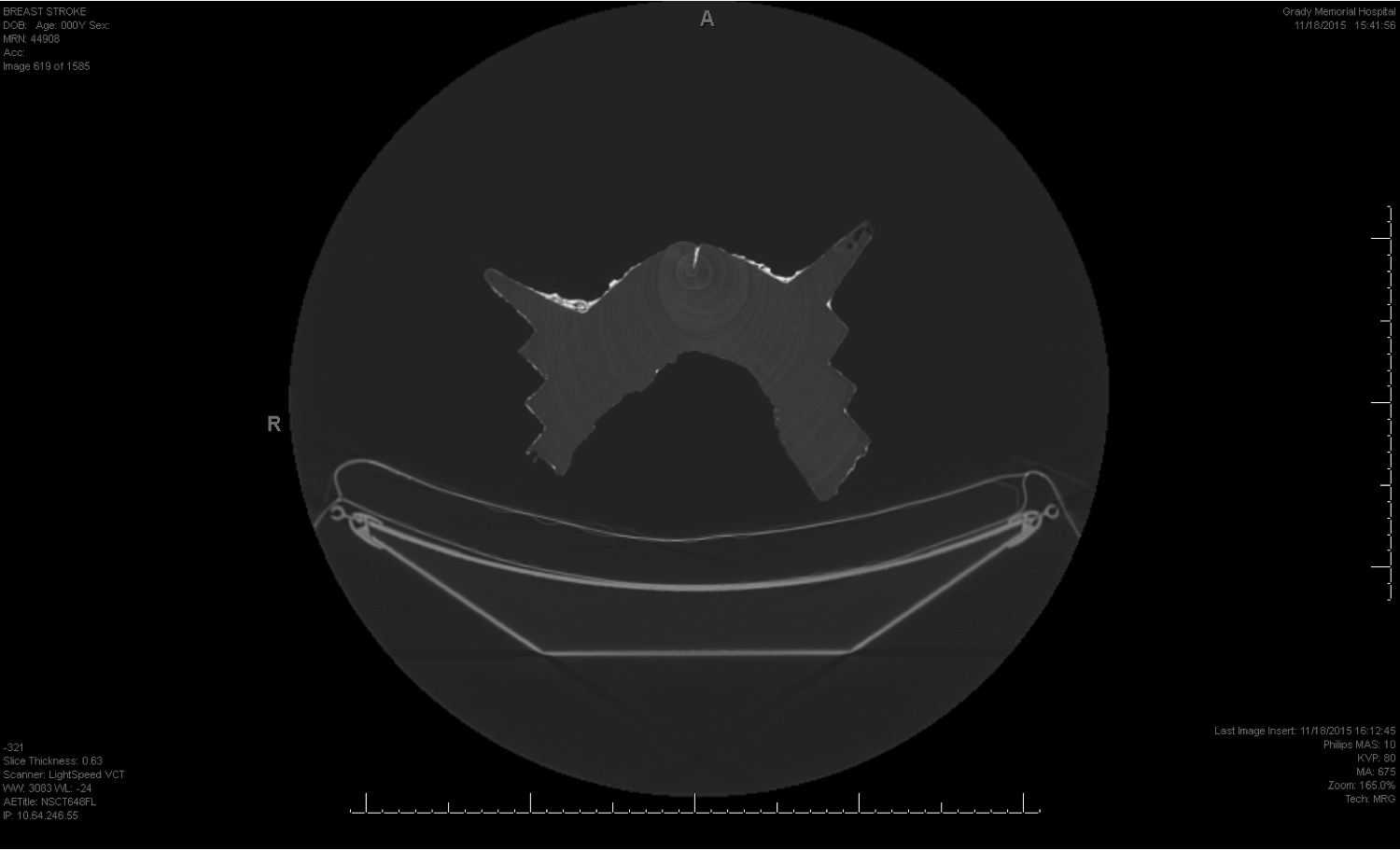

CT image showing cross-section of the mask sitting on scanner bed. The wood grain is visible, and the thick surface coating appears a bright layer between the mask’s ears.

CT image showing cross-section of the mask sitting on scanner bed. The wood grain is visible, and the thick surface coating appears a bright layer between the mask’s ears.

In order to learn more about the mask’s construction, we brought it to Grady Hospital in downtown Atlanta for CT scanning. Conservators often use this non-invasive tool to examine art objects, and as a biology and art history double major, I especially enjoyed this intersection of medicine and art. The full length X-rays show no joins, confirming that the mask’s creator used a single piece of wood. The cross-sections reveal the wood grain running lengthwise through the mask, with the center of the log located near the mask’s forehead.

A bundle of green and red woven fabric is attached to the mask’s upper jaw with copper wire and cord. As we examined the Carlos mask, we saw that the cords wrapping around the jaw are coated in surface material. The bundle is uncoated and open, with no visible evidence of the materials that might have been inside.

We noticed a dark patch between two small holes above the mask’s eyes. This dark patch absorbs UV light, suggesting it contains different materials from the light-colored surface layers around it.

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF), a non-destructive surface analysis technique used to determine elemental composition, revealed that the dark patch contains more copper than the surrounding area. The copper (Cu) peak is identified in this XRF spectrum from the dark patch above the eyes.

The copper peak could be residue from the copper wire that secured the bundle. In comparable helmet masks, bundles of powerful materials are positioned higher up on the forehead. This dark, copper-containing patch could be evidence that the bundle was moved from the forehead to the jaws. Since the cords on the jaw are coated, more surface materials may have been applied after the bundle was relocated.

We analyzed surface samples using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, or FTIR, which works by exposing samples to an infrared beam. Different types of chemical bonds respond predictably to this energy, and the resulting spectrum suggests the organic compounds present in the sample. This FTIR spectrum from a sample of the surface coating indicates the presence of amides and silicates.

FTIR spectra of samples from the Carlos Kono mask include amide peaks, indicating the presence of protein. While this result is informative, FTIR cannot identify the exact type of protein. Firsthand observations from art historians, anthropologists, and colonial officials in West Africa tell us that accumulative surfaces can contain several protein-rich materials, including hair, saliva, and animal blood.

To find out more about the proteins present on the mask’s surface, we took small samples to the Emory Integrated Proteomics Core for mass spectrometry. This technique separates components of mixtures by their different masses, so they can be identified individually. The scientists compared the results from the proteins found in the sample to a database of protein sequences from hundreds of species. Matches in the database showed that the proteins in the surface include hemoglobin, likely from goat and/or dog blood. Blood is a powerful substance in Kono ritual practice, and goat blood has been documented in the creation of Kono objects.

Conservators regularly combine scientific and art historical knowledge to investigate how art objects were constructed and used. This was my first technical investigation of a single object, and I appreciated the opportunity to learn more about the field of conservation. During this study, we learned a lot about the materials and construction of the Carlos Museum's Kono mask. We also noted evidence suggesting the relocation of the bundle and addition of more layers, reflecting a history of use.

The helmet mask is so far removed from its original context that we can never know everything about its history before it entered the Carlos Museum, but what we’ve learned has been fascinating.

Sources and further reading:

Fraser, Daniel, with Cathy Selvius DeRoo, Robert B. Cody, and Ruth Ann Armitage. “Characterization of blood in an encrustation on an African mask: Spectroscopic and direct analysis in real time mass spectrometric identification of haem.” Analyst 138 (2013): 4470-4474.

O’Hern, Robin, Ellen Pearlstein, and Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi. 2016. “Beyond the Surface: Where Cultural Contexts and Scientific Analyses Meet in Museum Conservation of West African Power Association Helmet Masks.” Museum Anthropology 39 (1): 70-86. DOI: 10.1111/muan.12102